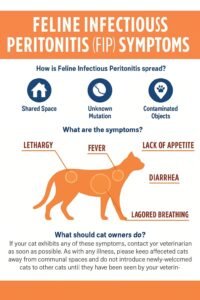

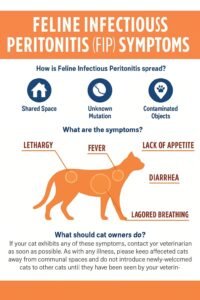

Feline Infectious Peritonitis, or FIP in cats, is a serious and often misunderstood disease caused by a mutation of a common virus found in cats—the feline coronavirus (FCoV). While most cats infected with FCoV show no symptoms or only mild digestive upset, a small percentage experience a rare mutation that turns the virus into feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV)—and that’s when things become life-threatening.

FIP symptoms can be subtle at first—a little lethargy here, a mild fever there—but can rapidly progress to severe illness if left unchecked. Knowing what to look for could quite literally save your cat’s life.

What Is FIP & How It Develops

Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) is a serious and typically fatal condition in cats, resulting from a mutated strain of the feline coronavirus (FCoV). It’s important to understand that not all feline coronaviruses are dangerous—FCoV is actually quite common, especially in multi-cat households, catteries, and shelters. In most cases, it causes no more than mild diarrhea or goes completely unnoticed.

However, in a small percentage of infected cats, the virus mutates inside the body—a process explained by what’s called the internal mutation theory. This theory suggests that rather than catching FIP from another cat, a feline already carrying the mild form of FCoV experiences a spontaneous mutation. Once this happens, the virus transforms into a more aggressive strain known as feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), which can then spread throughout the body and trigger a severe inflammatory response.

Which Cats Are Most at Risk?

Certain groups of cats are more vulnerable to developing FIP after exposure to FCoV:

- Kittens under 2 years old, due to their immature immune systems

- Purebred cats, especially those from catteries or breeders

- Cats in multi-cat environments, like shelters or foster homes

- Immunocompromised cats, such as those with FeLV or FIV

- Cats under chronic stress, which can weaken their immune defenses

Understanding how FIP develops—and knowing which cats are at greater risk—can help you stay alert to early symptoms and act quickly if something feels off.

Contagion & Transmission: Is FIP Contagious?

One of the most common—and confusing—questions I get from concerned cat parents is: “Is FIP contagious?” The answer requires some important nuance, so let’s break it down.

✅ FCoV is Contagious. FIPV is Not.

Feline coronavirus (FCoV)—the original, non-mutated virus—is highly contagious, especially in places where many cats share litter boxes, food bowls, or close living quarters. It spreads through the fecal-oral route, meaning a cat can become infected by grooming themselves after stepping in contaminated litter, or by sharing a space with an infected cat.

However, the mutated form that causes Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP)—known as FIPV—is not considered contagious in the traditional sense. According to the internal mutation theory, the transformation of FCoV into FIPV happens inside the body of an individual cat, not from direct transmission of FIPV between cats.

In short, cats catch FCoV, not FIP. FIP develops later, if and when the virus mutates.

How FCoV Spreads Between Cats

- Shared litter boxes (most common route)

- Shared food/water bowls

- Close contact or mutual grooming

- Contaminated hands, clothes, or bedding

- Introduction of new cats from FCoV-positive environments

The virus can survive on surfaces for several hours, especially in cool, dry conditions, making hygiene in multi-cat homes essential.

High-Risk Environments

- Shelters

- Breeding facilities

- Multi-cat households (especially >5 cats)

- Catteries or rescue fosters

- Stressful or unsanitary environments

Cats living in these settings are more likely to be exposed to FCoV, though not all will develop FIP. The risk increases if the cat is young, genetically predisposed, or immunocompromised.

Types of FIP & Symptom Differences

Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) appears in two main clinical forms—wet (effusive) and dry (non-effusive)—with a third mixed form occurring in some rare cases. Recognizing which type your cat may be showing signs of is vital, as the symptoms, progression, and diagnostic approach can differ significantly.

Wet FIP (Effusive Form)

This is the more common and faster-progressing form of FIP, often seen in younger cats. It’s characterized by a buildup of thick, yellowish fluid in the abdomen, chest, or both.

Key symptoms of wet FIP:

- Abdominal swelling or a “pot-bellied” appearance

- Difficulty breathing due to fluid in the chest (pleural effusion)

- Lethargy, weight loss, and fever

- Pale gums or signs of anemia

- Decreased appetite

The presence of fluid often leads to a dramatic and visible decline, which can be alarming for cat owners.

Dry FIP (Non-Effusive Form)

Dry FIP develops more slowly and does not involve fluid accumulation. Instead, it causes granulomatous inflammation in various organs, including the eyes, brain, kidneys, and liver. This form is trickier to diagnose because the symptoms are often vague and systemic.

Key symptoms of dry FIP:

- Neurological signs: head tremors, loss of coordination, seizures, or behavioral changes

- Ocular signs: changes in eye color, cloudiness, uveitis, retinal detachment

- Weight loss, persistent fever, poor appetite

- Organ dysfunction: enlarged lymph nodes, jaundice, irregular liver/kidney values

- Anemia and chronic lethargy

Mixed FIP (Rare)

In rare cases, cats can exhibit signs of both wet and dry FIP. For instance, a cat might have fluid in the abdomen and neurological or ocular symptoms simultaneously. These mixed presentations complicate diagnosis but are increasingly documented in clinical studies.

Early & Non‑Specific Warning Signs

One of the biggest challenges in diagnosing FIP early is that the initial symptoms are subtle and easily mistaken for other illnesses. Many cat owners overlook the early signs—especially in the dry form—until the disease has progressed.

General Early Symptoms to Watch For:

- Lethargy or fatigue

- Loss of appetite (anorexia)

- Weight loss or failure to thrive

- Persistent or recurring fever, often unresponsive to antibiotics

- Pale gums or anemia

Behavioral Red Flags

Changes in behavior can also be an early indicator, especially in cats with neurological involvement:

- Hiding more than usual

- Sudden aggression or withdrawal

- Unusual appetite patterns, like chewing on inedible objects (pica)

- Vocal changes or confusion

Why These Symptoms Matter

These vague signs may seem minor at first, but in the context of high-risk cats (young, purebred, shelter-raised) they warrant immediate attention. Early veterinary evaluation, bloodwork, and imaging can make a huge difference in survival, especially now that newer antiviral treatments are available.

Organ‑Specific & Advanced Signs of FIP in Cats

As Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) progresses—especially in non-effusive (dry) and mixed forms—it begins to affect specific organs and body systems. These advanced symptoms can vary depending on which organs are inflamed or compromised by the immune-mediated response triggered by the FIP virus (FIPV).

Neurological Signs

When FIP reaches the central nervous system, the results can be devastating. These symptoms are more common in dry FIP and tend to progress rapidly once they appear:

- Ataxia (uncoordinated movements or staggering)

- Head tremors or twitching

- Seizures

- Partial or full paralysis

- Disorientation or behavioral changes

If you notice your cat walking like they’re “drunk,” falling over, or having trouble jumping, seek veterinary care immediately.

Ocular (Eye-Related) Symptoms

Ocular involvement is another hallmark of dry FIP. The eyes may become visibly inflamed or show subtle signs of vision loss:

- Uveitis (painful eye inflammation)

- Cloudy eyes or a change in iris color

- Retinal detachment or hemorrhage

- Unequal pupil size or vision difficulty

These symptoms can be mistaken for other eye diseases, which is why a full systemic evaluation is critical when FIP is suspected.

Respiratory & Abdominal Distress

Seen most often in wet (effusive) FIP, fluid accumulation can cause major discomfort and life-threatening complications:

- Labored breathing (dyspnea) due to fluid in the chest

- Abdominal distension from peritoneal fluid buildup

- Weakness and collapse, especially after mild exertion

Thoracentesis (removal of chest fluid) or abdominocentesis can temporarily relieve symptoms and aid diagnosis.

Liver & Gastrointestinal Involvement

As the liver becomes inflamed (hepatitis) or enlarged (hepatomegaly), you may see:

- Jaundice (yellowing of gums, ears, or eyes)

- Chronic diarrhea or soft stool

- Poor digestion and nutrient absorption

- Elevated liver enzymes in lab work

Cats in this stage often become visibly thin despite eating and may develop a sour-smelling breath due to toxin buildup.

Final/Terminal Stage Features of FIP

In the final stages, FIP overwhelms the cat’s immune system and critical organs, leading to multi-system failure. These signs typically emerge within days to a few weeks after severe symptoms begin, particularly in kittens and young cats:

- Severe breathing distress, even at rest

- Full or partial paralysis

- Inability to walk, stand, or control limbs

- Urinary or fecal incontinence

- Seizures or coma-like unresponsiveness

- Rapid decline in body condition and temperature

- Failure of multiple organs, including the kidneys, liver, and lungs

Sadly, at this point, euthanasia is often the kindest option unless the cat is already receiving antiviral treatment (such as GS-441524 or remdesivir) with an early response.

⏱️ Typical timeline: In young kittens or high-risk cats, death can occur within 2 to 4 weeks after the onset of major symptoms—sometimes even sooner in wet FIP.

How Did an Indoor Cat Get FIP?

If your cat lives strictly indoors, it’s natural to wonder: “How could this happen?” Unfortunately, being inside doesn’t make a cat immune to FCoV exposure, especially when we consider the virus’s stealthy and persistent nature.

Indoor Cats Can Still Get FIP — Here’s How

FIP doesn’t develop from exposure to the mutated virus itself, but from exposure to feline coronavirus (FCoV)—a typically mild virus that can mutate inside your cat’s body into FIPV.

Even indoor cats can encounter FCoV in subtle ways:

- Carriers brought in from shelters, breeders, or foster situations

- Asymptomatic cats in the home are shedding the virus unknowingly

- Fomites (virus particles carried in on shoes, clothing, hands, bedding, or food containers)

- Human traffic from multi-cat homes or vet clinics

This virus is surprisingly resilient in litter and environments where proper hygiene is lacking. You won’t see it, but it could be hitching a ride on your pant leg.

Once FCoV is in your home, your cat may carry the virus for weeks or months before showing any signs—or they may never show signs at all. In a small percentage of cases, the virus mutates spontaneously, resulting in FIP. That mutation is unpredictable and not your fault.

Diagnosis: What Vets Do to Confirm FIP

Diagnosing FIP is one of the most challenging tasks in feline medicine. There’s no single test that says “yes” with 100% certainty, especially for the dry form. Instead, vets piece together evidence through a combination of tests, symptoms, and imaging.

Standard Diagnostic Tools

Here’s what your veterinarian may recommend to diagnose FIP:

- Complete bloodwork (CBC & biochemistry) – Looks for anemia, high globulins, low albumin, elevated liver enzymes, or lymphopenia

- Abdominal or chest fluid analysis (for wet FIP) – FIP fluid is usually thick, straw-colored, and high in protein

- Ultrasound or X-rays – May reveal fluid buildup, enlarged organs, or lymph nodes

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) – Detects FCoV RNA in fluid, blood, or tissue; highly sensitive but not definitive alone

- Immunocytochemistry / IHC – Identifies FIP virus inside macrophages in fluid or tissue (gold standard when positive)

- Ocular and CSF fluid analysis (for neurological or eye signs) – Used to confirm dry FIP with central nervous system involvement

- Histopathology (biopsy) – Examines tissue from affected organs for FIP-characteristic lesions

For wet FIP, fluid testing and imaging often provide clearer clues.

For dry FIP, diagnosis is often a process of exclusion, relying on systemic symptoms and multiple tests over time.

Treatment Options for FIP in Cats

Until a few years ago, a diagnosis of FIP was considered a death sentence. But today, we finally have real hope, thanks to breakthrough antiviral medications and supportive therapies that are saving cats’ lives around the world.

Antivirals: GS-441524 & Remdesivir

The gold standard treatment for FIP is GS-441524, a nucleoside analog that targets viral replication. It has demonstrated over 80% survival rates, especially when started early. In the U.S., this drug is not formally FDA-approved, but as of June 2024, it is legally available under “enforcement discretion,” allowing compounding pharmacies and veterinarians to access and prescribe it.

Remdesivir, a prodrug of GS-441524, is sometimes used intravenously for severe cases or neurological FIP, especially at the beginning of treatment.

- Typical course: 12 weeks of oral or injectable antiviral treatment

- Response timeline: Many cats improve within days of starting therapy

- Access: Some U.S. clinics and veterinary pharmacies now offer GS-based formulations legally (check with your vet or local compounding pharmacy)

🧪 Note: Early diagnosis and prompt antiviral treatment dramatically improve the outcome, especially in kittens and wet FIP cases.

Other Antivirals Under Study

- GC376: A protease inhibitor showing promise in clinical trials, though less widely used

- Molnupiravir: An oral antiviral used experimentally in some rescue settings; not yet a standard treatment but being explored as a cost-effective alternative

Immune-Modulating Support

Some cats benefit from adjunct therapies that support the immune system or reduce inflammation:

- Feline interferon-omega: Antiviral immune booster used more in Europe and Japan

- Polyprenyl immunostimulant: Sometimes used in dry FIP with mild symptoms, though evidence is limited

- Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisolone): Help reduce inflammation and discomfort, but do not treat the virus—only used in palliative or transitional care

These treatments may be combined with antivirals to support systemic recovery, manage flare-ups, or reduce neurological inflammation.

Prognosis & Long‑Term Outlook for Cats with FIP

Without Treatment

Historically, FIP has been almost universally fatal, especially the wet form. Most untreated cats deteriorate rapidly once major symptoms set in—often within 1–4 weeks. Dry FIP may stretch longer, but eventually leads to organ failure or neurological decline.

Palliative care may extend comfort for a short time, but survival without antiviral treatment is extremely rare.

With Antiviral Treatment

With access to GS-441524 or remdesivir, the long-term outlook has changed dramatically:

- Survival rates are>80% when treated early and appropriately

- Many cats return to normal life post-treatment—active, playful, and symptom-free

- Even neurological and ocular FIP cases now have strong recovery potential with high-dose protocols

- Post-treatment monitoring is key: bloodwork, weight checks, and behavioral observation for at least 3–6 months after completion

As of June 2024, real-world access in the United States is expanding thanks to relaxed FDA enforcement and support from licensed compounding pharmacies. This is a huge step forward for both vets and pet parents.

Prevention & Owner Tips

Although there’s no guaranteed way to prevent FIP—since it results from an internal mutation of feline coronavirus (FCoV)—there are several practical strategies that cat owners can follow to reduce both exposure and risk. The most important step is maintaining excellent hygiene, especially in multi-cat homes where FCoV tends to spread more easily. Cleaning litter boxes daily, using separate boxes for each cat, and disinfecting feeding areas regularly can help minimize viral transmission. It’s also important to keep stress levels low, as chronic stress weakens a cat’s immune system and may increase the likelihood of FCoV mutating into FIP. Providing plenty of enrichment, personal space, and a stable routine can go a long way in protecting your cat’s overall health.

Introducing new cats should always be done with care. Quarantine any new arrival for at least two weeks, and watch for signs of illness, especially gastrointestinal issues like diarrhea, which could indicate FCoV shedding. Even indoor-only cats can be exposed through contaminated objects—like shoes, clothing, or carriers—so good biosecurity practices are helpful, particularly if you’ve been in contact with other cats.

While there is a vaccine for FIP, it’s not widely recommended. According to the American Association of Feline Practitioners, the intranasal FIP vaccine has limited effectiveness and is unlikely to protect cats already exposed to FCoV, which includes the majority of adult cats by the time they’re eligible for vaccination. Instead, focusing on hygiene, stress reduction, and early detection remains the most effective strategy for reducing your cat’s risk of developing FIP.

Learn about Cat flu.